For fifty years, Evergreen Treatment Services has had the privilege of serving the greater Puget Sound community. Since first opening its doors in 1973, much has changed about ETS. But one thing has remained the same: we put the needs of those we serve first. For ETS, care is evergreen.

Tom Odell was ETS’s first executive director. He founded the organization, first called Central Breakthrough Maintenance Program, two years into Nixon’s declaration of the war on drugs. Fifty years later, Tom is still working in harm reduction. We were honored to sit down with Tom and hear about the stigma patients faced and what it was like building a treatment center that prioritized client dignity.

Donate to ETS to support our life-saving work.

It’s easy for Tom Odell to remember the year he started what is now Evergreen Treatment Services: it’s the same year as his wedding anniversary. In 1973, there were just two methadone treatment centers in the broader Puget Sound region, and it was a “totally new field.” One of these clinics, Seattle Treatment Center, had filed for bankruptcy. Art Simmons, then the executive director at the Center for Addiction Services in Seattle, approached Tom. Given his prior experience working with methadone clinics, Art asked Tom to retain the staff from the closing clinic and begin a new treatment center.

At 26 years old, Tom put together a board of directors and kept the majority of the staff from Seattle Treatment Center, including four counselors who had experienced harmful substance use themselves. Tom created a program with board representation of patients, including a voting process to determine a spokesperson for the patient population. He recalls a few ecstatic patients in the program who joined the board.

Central Breakthrough Maintenance Program incorporated on May 21, 1973. ETS’s original name was chosen by patients, with one patient in particular who was especially vocal that the organization’s name represent a combination of its services and its original central Seattle location.

Back in the 70s, the public was much less understanding and accepting of methadone treatment. Stigma against patients receiving methadone was similar to stigma against people struggling with alcohol use at the time—the overall narrative was that “anybody who used drugs was a bad person.” The public believed that people who were dealing with a substance use disorder were at fault—a common misconception ETS continues to combat today. There were unfounded fears, exacerbated by the media, that people using substances would steal or hurt others. These were “misunderstandings of human nature,” as Tom refers to them.

Tom equates this all-or-nothing mentality to one expressed in Barbara Kingsolver’s “Demon Copperhead,” a story about rural West Virginia in the modern day. The book delves into how difficult it is for someone to get out of the environment they’re in when it is all they have ever known. “There’s this sense that people are still fully responsible for their own behaviors,” Tom explains. “But how do you get out of the ‘wrong’ part of society when you have nothing else?”

Tom notes that medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and outreach models are much more accepted now, though there is still lingering stigma around harm reduction approaches. For example, insurance companies often don’t accept safe injection sites as legitimate. “Methadone,” he says, “was in the same boat 50 years ago.” The Central Breakthrough Maintenance Program team spent a significant amount of time and money proving to the Drug Enforcement Administration that methadone was an effective treatment option. It was perceived to be “a big waste of money” despite its positive impact on patients, and Tom recounts how the organization spent nearly 60% of its funds on record keeping. Funding was unpredictable in those early days. Most years, it would be somewhat secure from January through December, but “December 20 would roll around and we didn’t know whether we would have a contract in January.”

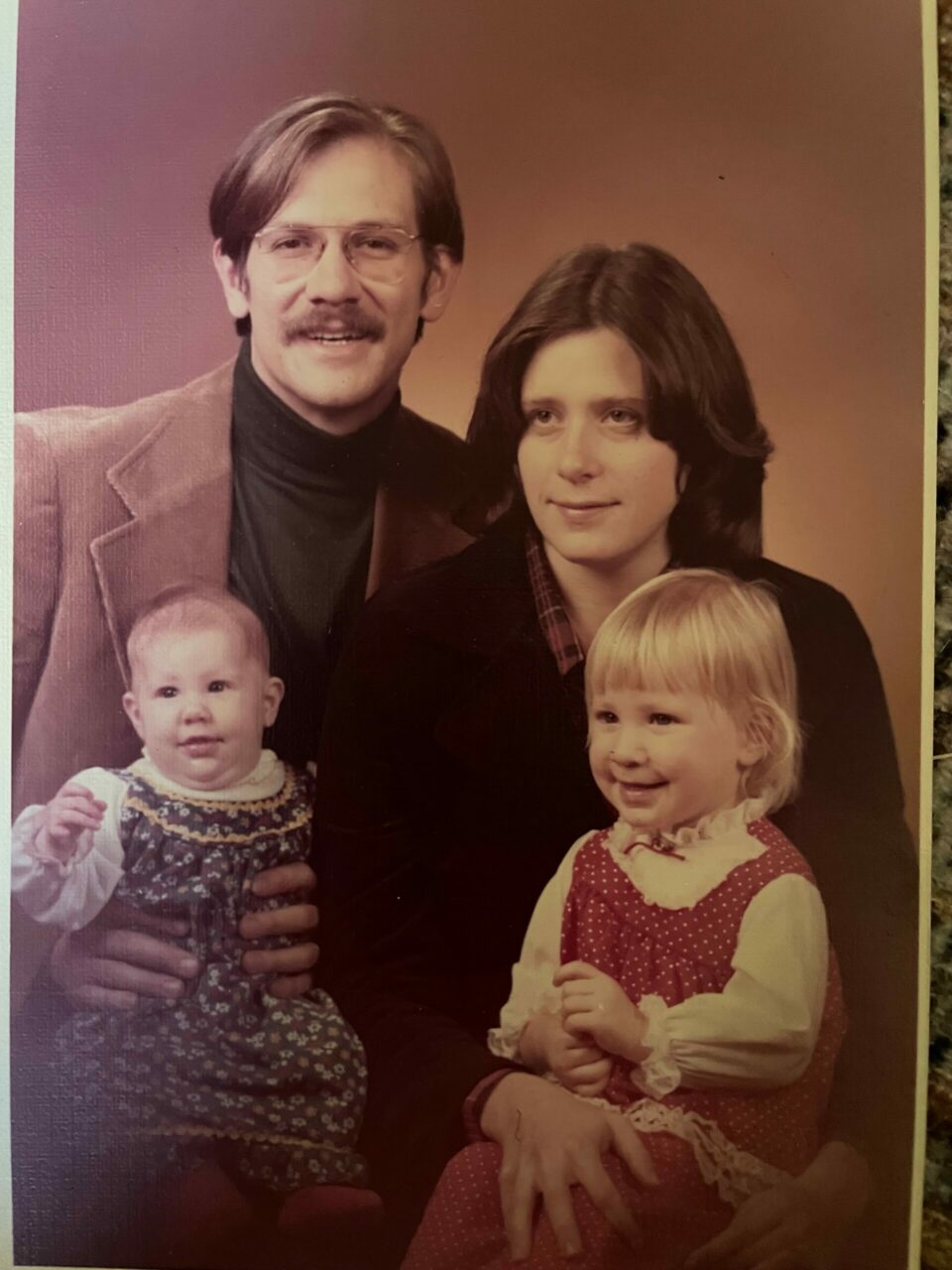

Throughout his initial involvement in the harm reduction community, Tom noticed that some people felt they had to be “tough” on patients. He disagreed. Tom regularly brought his 2-year-old daughter into the clinic while he was executive director. Patients would come in to hold her and talk with her. To others, this was an odd and risky decision—public discourse stigmatized people using substances and claimed they were dangerous. But Tom acted on what he knew: that folks receiving treatment deserved respect. Introducing patients to his daughter was merely one way he honored and demonstrated mutual trust among those he served.

Tom continued to work in harm reduction and still advocates for safe injection sites. He also helped start Genesis House, a program providing residential services to people receiving methadone treatment that operated for 30 years. If he’s learned anything from his seven years spent establishing Central Breakthrough Maintenance Program, it’s the power of treating people like people.

While conducting outreach, Tom recalls receiving feedback from a client 25 years after the fact. “There was a patient once who had success in treatment and got to the point where he moved to California and became a counselor himself. Well, while he was out there, he made connections in the harm reduction community and connected with someone and somehow, I came up in conversation. Turns out they both knew me! Twenty-five years later and they still remembered me. I know this because I received a thank you note from them. My former patient thanked me for treating him like a person while he was in treatment. Treating someone with respect and dignity goes a long way.”

Today, Tom has four grandchildren, his “most wonderful accomplishment.” His second proudest achievement, though, is starting Central Breakthrough Maintenance Program. “I’m not just proud of the business,” he clarifies, “but proud of the harm reduction in the smallest moments.”

Tom was an excellent leader and did follow his heart in respect of others regardless of station